Introduction

Have you ever had an email you needed end up in your spam folder? Or too much spam getting into your inbox?

This is a problem that almost everyone faces. Based on this simple spam classifier model example, you’ll be able to see why this problem exists. Most spam classifiers simply take into account what words appear in the email and how many times they appear. Spam creators have gotten clever to add hidden words that will trick a classifier.

To better understand a simple classifier model, I’ll show you how to make one using Natural Language Processing (NLP) and a Multinomial Naive Bayes classification model in Python.

Loading Data

I got my dataset from the UCI Machine Learning Repository. This dataset includes messages that are labeled as spam or ham (not spam).

To begin, start by importing some necessary packages:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

and load in your data:

df = pd.read_csv('smsspamcollection/SMSSpamCollection.txt', sep = '\t', header = None)

df.columns = ['label', 'text']

and previewing your DataFrame:

df.head()

You should see the following table:

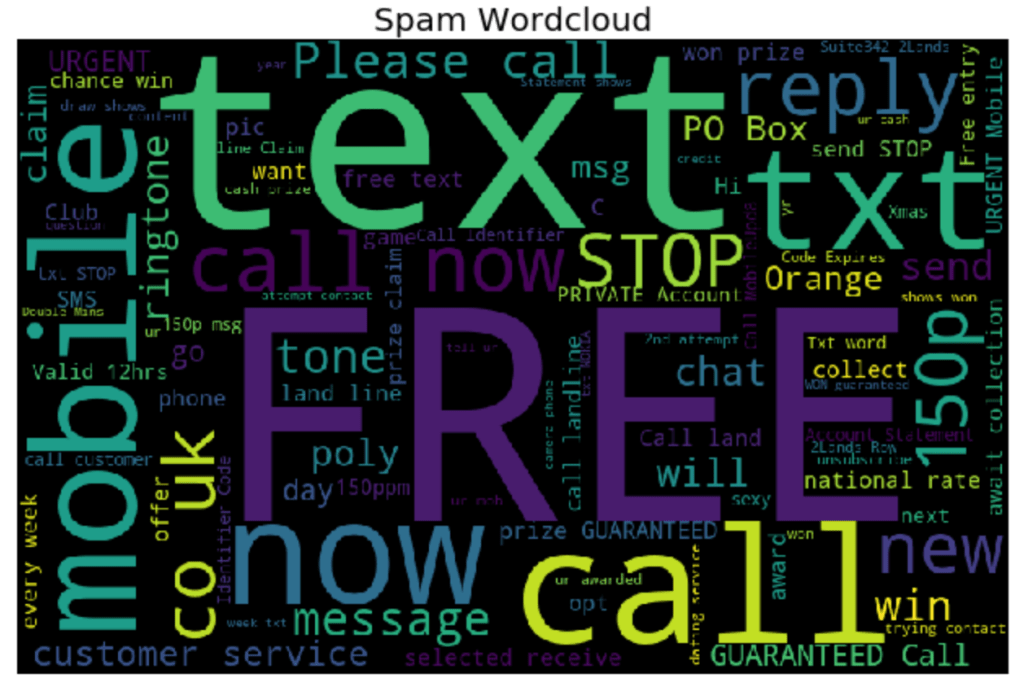

Data Visualization

Let’s start by looking at our data in Word Clouds based on spam or not spam (ham). First import more useful packages:

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize

from nltk.stem import PorterStemmer

from wordcloud import WordCloud

import string

Now create the spam word cloud:

spamwords = ' '.join(list(df[df.label == 'spam']['text']))

spam_wc = WordCloud(width = 800, height = 512, max_words = 100, random_state = 14).generate(spamwords)

plt.figure(figsize = (10, 6), facecolor = 'white')

plt.imshow(spam_wc)

plt.axis('off')

plt.title('Spam Wordcloud', fontsize = 20)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

and now create the ham word cloud:

hamwords = ' '.join(list(df[df.label == 'ham']['text']))

ham_wc = WordCloud(width = 800, height = 512, max_words = 100, random_state = 14).generate(hamwords)

plt.figure(figsize = (10, 6), facecolor = 'white')

plt.imshow(ham_wc)

plt.axis('off')

plt.title('Ham Wordcloud', fontsize = 20)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

You should get the following two word clouds if you use the same random_state:

Text Preprocessing

Now we’ll have to create a text preprocessing function that we will use later on in our CountVectorizer function. This function will standardize words (lowercase, remove punctuation), generate word tokens, remove stop words (words that have no descriptive meaning), create bigrams (combination of two words i.e. "not good"), and find the stem of each word.

def message_processor(message, bigrams = True):

# Make all words lowercase

message = message.lower()

# Remove punctuation

punc = set(string.punctuation)

message = ''.join(ch for ch in message if ch not in punc)

# Generate word tokens

message_words = word_tokenize(message)

message_words = [word for word in message_words if len(word) >= 3]

# Remove stopwords

message_words = [word for word in message_words if word not in stopwords.words('english')]

# Create bigrams

# Add grams to word list

if bigrams == True:

gram_words = []

for i in range(len(message_words) + 1):

gram_words += [' '.join(message_words[i:(i + 2)])]

# Stem words

stemmer = PorterStemmer()

message_words = [stemmer.stem(word) for word in message_words if (len(word.split(' ')) == 1)]

# Add grams back to list

if bigrams == True:

message_words += gram_words

return message_words[:-1]

Now use CountVectorizer to create a sparse matrix of every word that is in the dataset after applying the text processing function created above:

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

X_vectorized = CountVectorizer(analyzer = message_processor).fit_transform(df.text)

Train Test Split

Now the data needs to be split into train and test sets for fitting and evaluating the model. I’ve chosen to set aside 20% of the data for testing and have used a random_state for reproducibility.

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X_vectorized, df.label, test_size = .20, random_state = 72)

Fitting the Naive Bayes Model

Now it’s time to fit the spam classifier model. In this case I will be using a Multinomial Naive Bayes. The Naive Bayes model in this case is looking at the probability of a message being spam given a certain word shows up in the message. Looking back to the generated word clouds, a message with the word "FREE" will have a high probability of being spam.

from sklearn.naive_bayes import MultinomialNB

MNB_Classifier = MultinomialNB()

model = MNB_Classifier.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_hat_test = MNB_Classifier.predict(X_test)

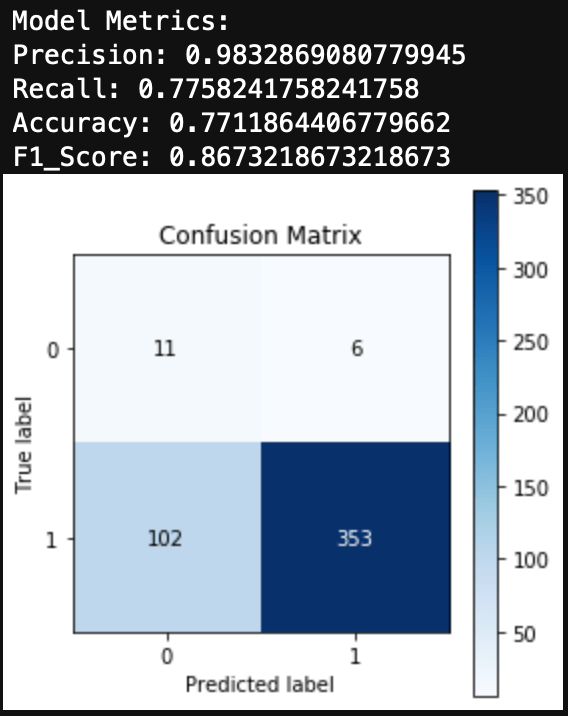

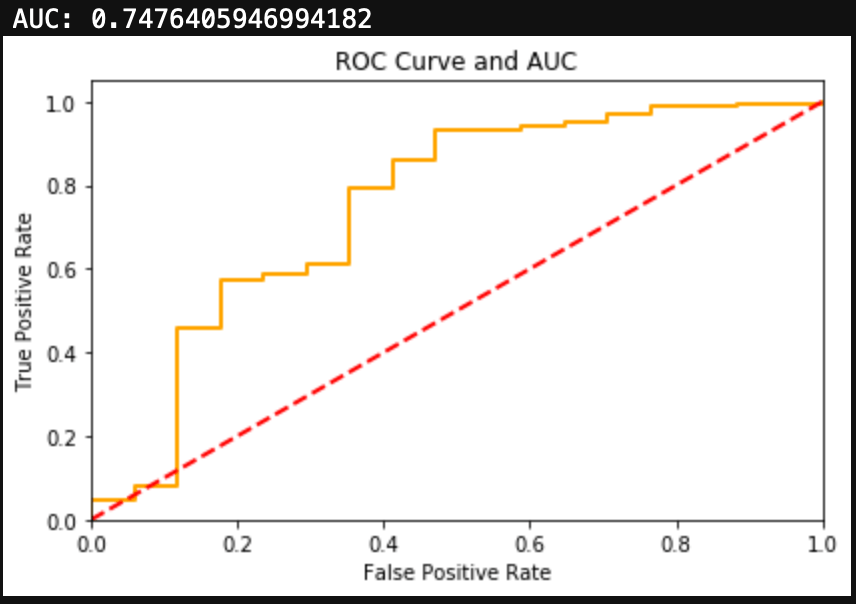

Evaluating the Model

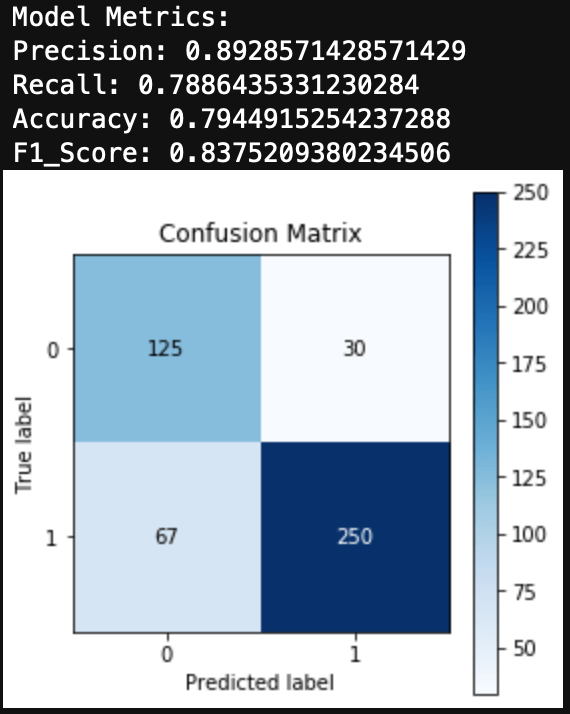

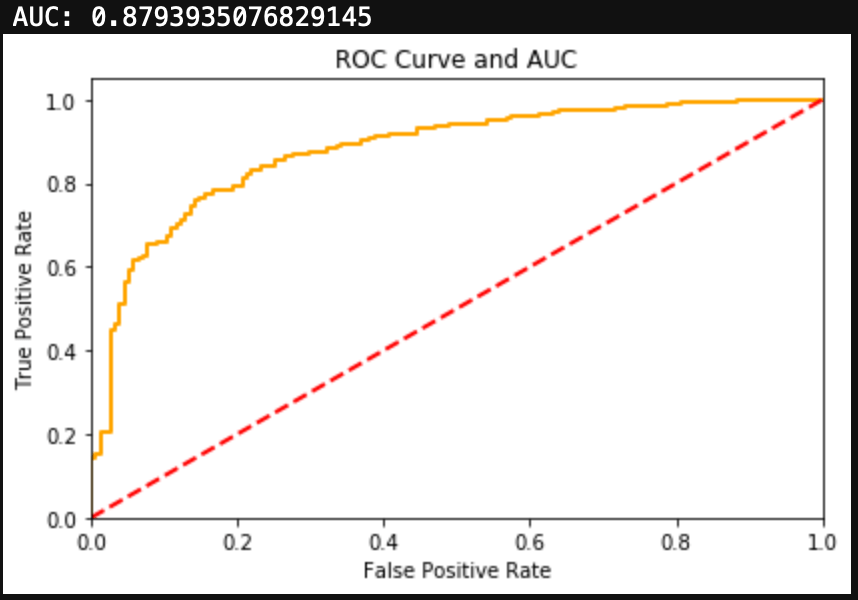

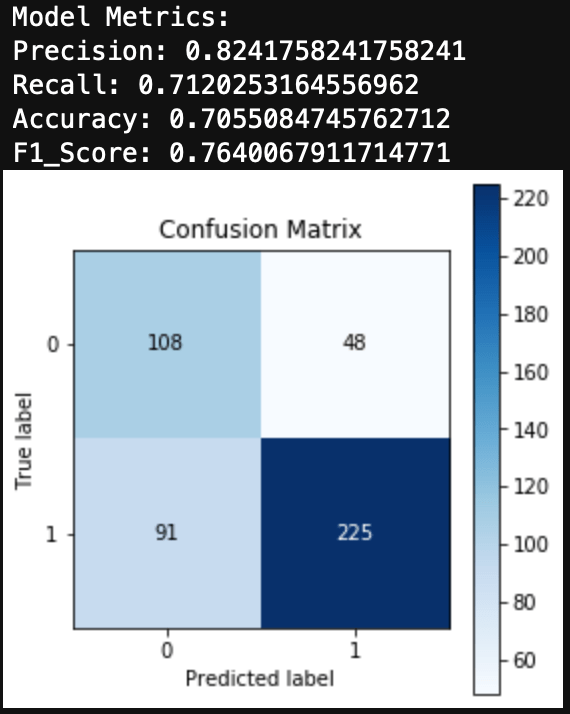

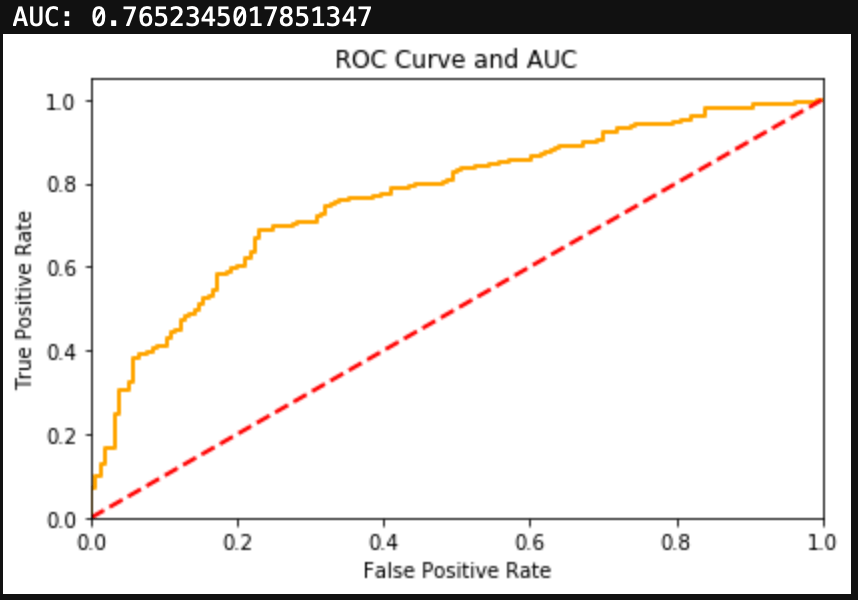

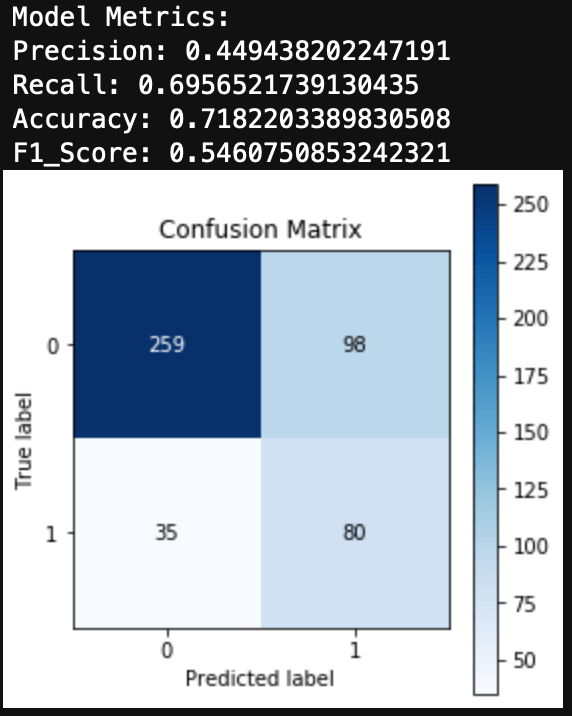

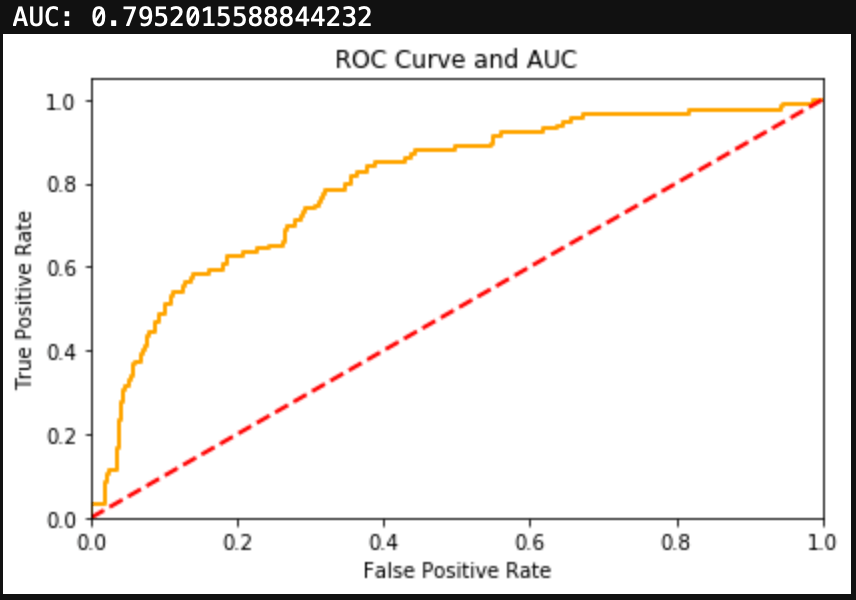

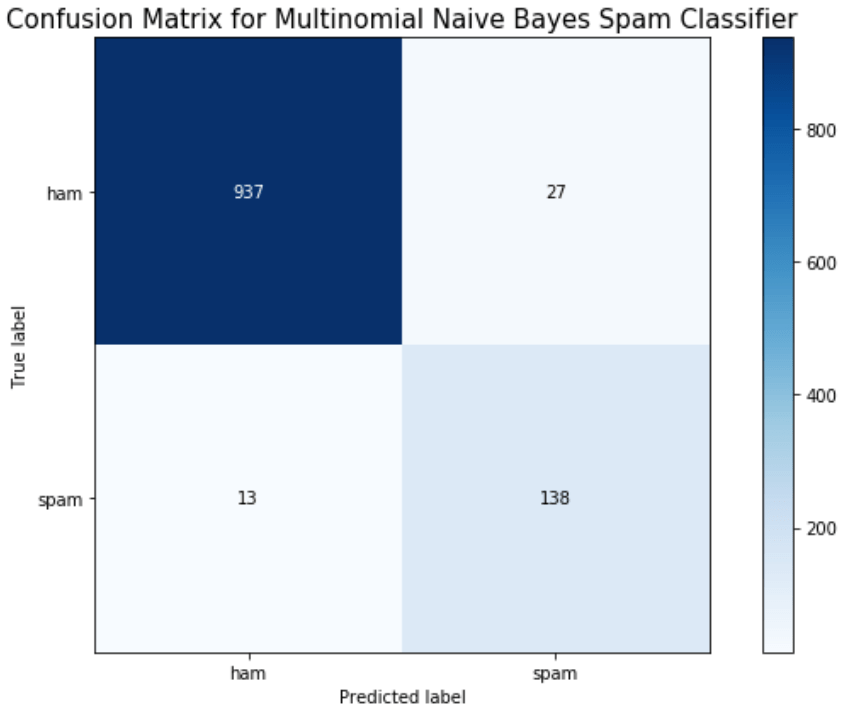

Finally, we can evaluate the model by looking at the classification report, accuracy, and a confusion matrix.

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report, confusion_matrix, accuracy_score, precision_score, recall_score, f1_score

print(classification_report(y_test, y_hat_test))

print('Accuracy: ', accuracy_score(y_test, y_hat_test))

import scikitplot as skplt

skplt.metrics.plot_confusion_matrix(y_test, y_hat_test, figsize = (9,6))

plt.ylim([1.5, -.5])

plt.title('Confusion Matrix for Multinomial Naive Bayes Spam Classifier', fontsize = 15)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Conclusion

We can see here that a Naive Bayes model works very well as a spam classifier. This is a very simple spam classifier, yet it still gets high metrics. However, the model is exposed to spammers who think a little more creatively. If a spammer was to include a lot of words (maybe even just hidden in the background) that typically appear in non spam messages, it could trick the model.