The Bootcamp Unwanted Repo Struggle

As a student in the Flatiron School Data Science Immersive Program in Chicago, I have encountered a problem that I believe many other tech bootcamp students have likely encountered: Hundreds of unwanted Github repositories. This problem came about because of the many online labs we have to complete as students. Anytime a repository is cloned in order to work on the lab locally, it creates a new repository on your Github account. As I am approaching the beginning of my career search, I wanted to clean up my Github page for potential employers to view. These employers will not want to have to search through 200+ repos in order to find the five repos I actually want them to see. Unfortunately, in order to delete a single repository on Github it requires clicking through about three pages, manually typing in the exact repository name you want to delete, and clicking again to finally delete. So you can see how this would get tiresome after about five repos. I wanted to find a way to automate this process to save myself the trouble.

Finding a Solution

Through the course of my internet searching for a solution, I came across this blog by a former Flatiron student facing the same problem. The blog, by Colby Pines, explains a solution to this problem using a Github API key and a bash function. I followed this blog, and it worked out great, but it left out some key steps/explanations, so I wanted to expand on the idea.

Cleaning your Github Page

Here are some steps to follow to clean out unwanted repos:

- Get a Github API token (Settings -> Developer settings -> Personal Access Tokens -> Generate New Token)

- Be sure to enter in a Note

- Check the repo and delete_repo boxes under "Select Scopes"

- Generate Token

- At this point you will get an API token. Be sure to copy this to a file so you don’t lose it

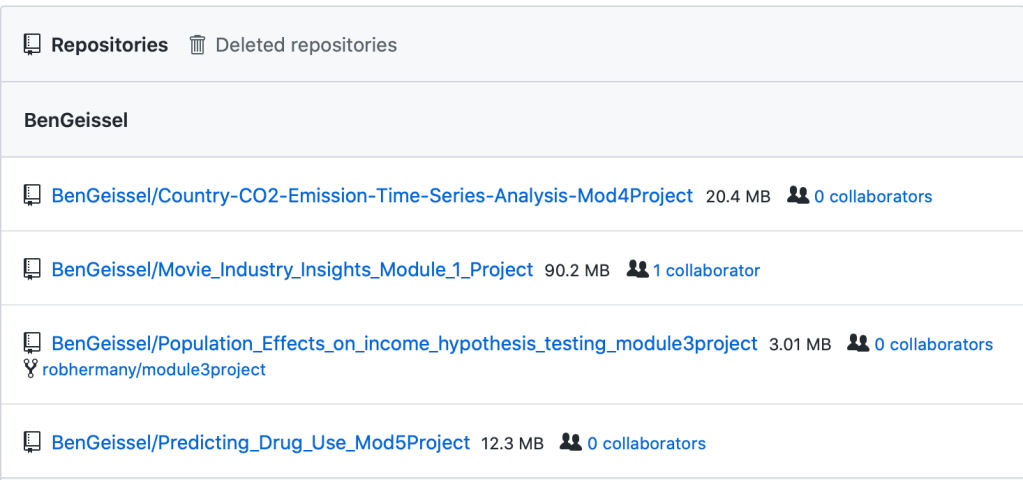

- Copy all your repos (Settings -> Repositories) and paste them into your favorite text editor (I use Atom)

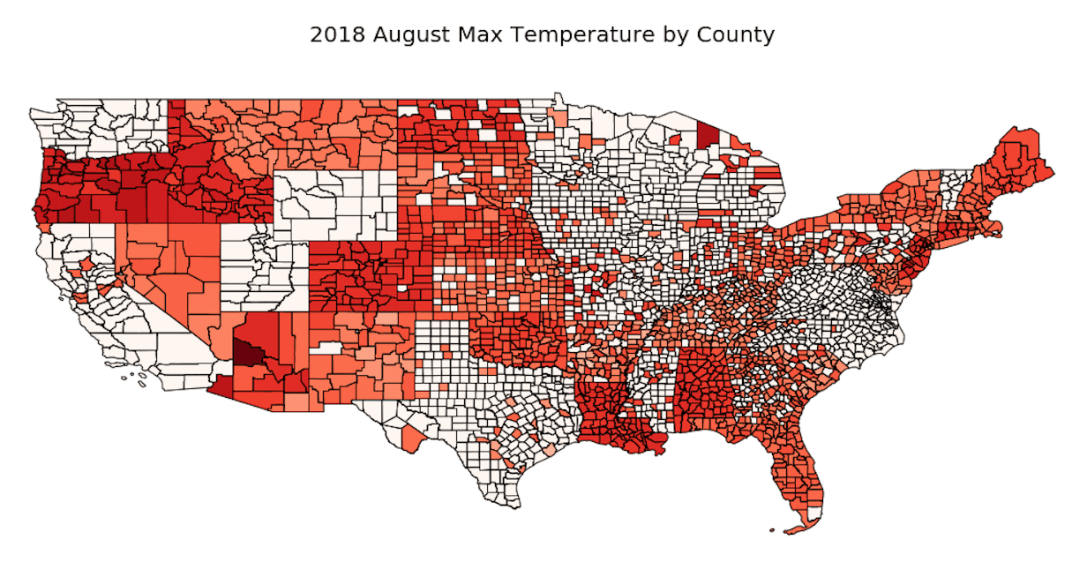

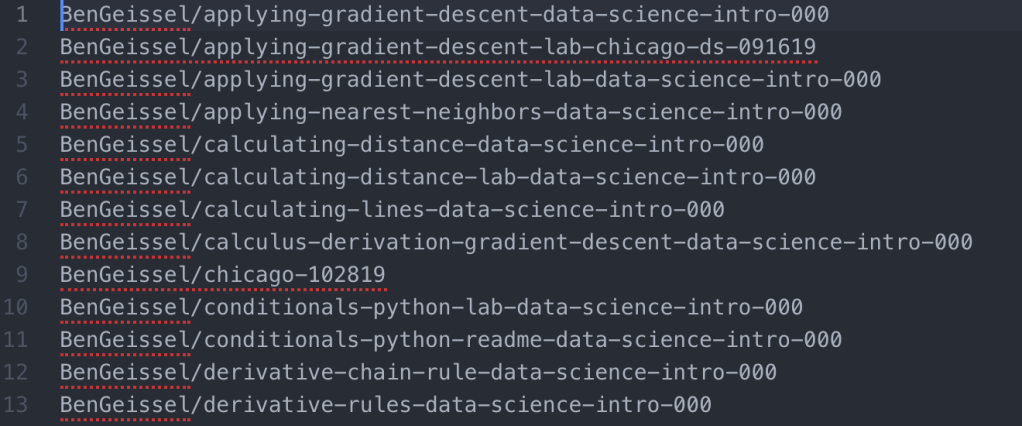

- The Repositories page should look something like the following. You can copy all of the list out into your text editor

- Use regex to filter the list down to just the ones you DO NOT want

- This site shows how to use regex with Atom

- I first searched for rows with learn-co (this is where Flatiron repos come from) and deleted these rows

- I next used Colby’s regex example for getting rid of all information after the repo name (each is followed by whitespace and size, collaborator information): %s/\s.*$//g

- At this point, you should be left with a list of repo names that you DO NOT want, separated by a new line. Save this file somewhere easy to access and name it unwanted_repos.txt (so you can remember what it is)

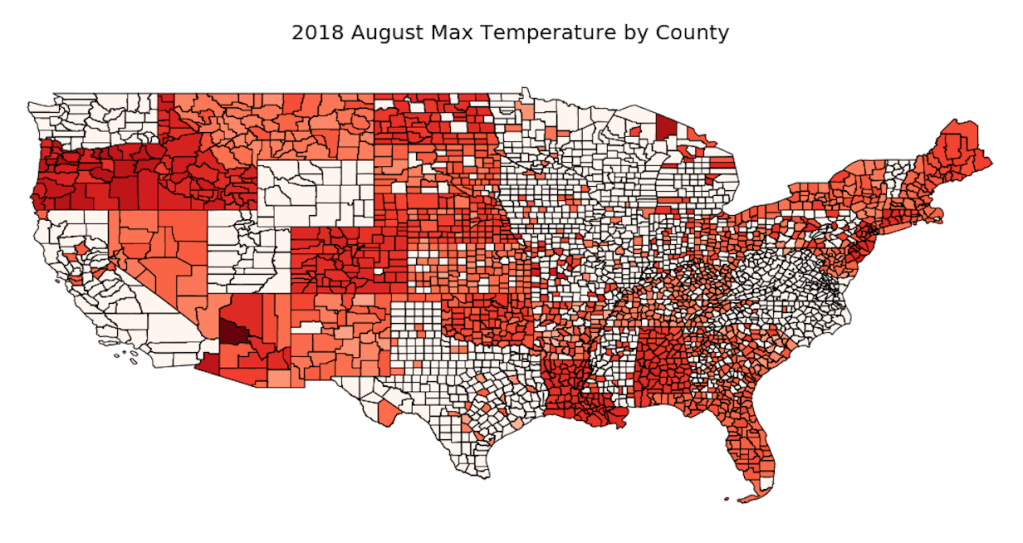

- The file should look something like this:

- Now we will shift to the terminal/command line. I use a Mac and utilize my bash profile for reference. First, you will want to find your bash profile by going to your root directory and opening up the bash profile with a text editor. I did this with the following code:

cd ~

atom .bash_profile

- Once in the bash profile we can add the following function that Colby created:

function git_repo_delete(){

curl -vL \

-H "Authorization: token YOUR_API_TOKEN_HERE" \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-X DELETE https://api.github.com/repos/$1 \

| jq .

}

In the above code, the $1 represents the unwanted repository name that will be inputed when the function is run.

NOTE: If the "jq" portion of this code does not work for you, brew install this through your terminal

brew install jq

- Once the function is saved in your bash profile you’ll be ready to run the final lines of code. In order for the function to work though, you’ll have to quit your terminal and restart it. Putting the function in the bash profile works because your terminal automatically sources the information in the bash profile when it starts up. If you want to put the function somewhere else, you will have to manually source that file after you save the function.

- After restarting your terminal (or sourcing your function from another file) you can run the following two lines of code:

repos=$( cat ~/Desktop/unwanted_repos.txt)

for repo in $repos; do (git_repo_delete "$repo"); done

- Make sure to change the path in the first line of code to where your unwanted repos list is saved.

- Once the second line of code is run, your terminal will iteratively delete each repo from your Github page. Check your Github page to make sure you now only have the repos you wanted left

Hope this helps! Thanks Colby for the original run through of this process!